Rung five – official pump demo – Animas Vibe

Yesterday we had a 4pm meeting with our local Animas representative Emma at our the hospital. It was Emma’s first meeting with the Paediatrics Diabetes Team at Winchester and that meeting had happened earlier yesterday, which is why I tagged ours on afterwards. Jane and Amy were travelling up separately from another direction.

Jane and I had already had a great demo of an Animas Vibe from Annie a couple of weeks back, but this would be Amy’s first demo, although she’d played with a similar pump earlier.

The RHCH hospital in Winchester only has a couple of adults using an Animas pump, if we go for it Amy will be the first child with one.

Like a blind date

It was funny though, like a blind date where literally I had no idea what Emma looked like. We’d arranged to meet in Costa at the hospital, but it’s large enough Costa to get lost in. I was first in – Jane/Amy were coming separately – followed in by two ladies. I got a coffee, they sat down, and I scanned them – hey, no, not like that! – looking for Animas logos/words/bags but nothing. So that wasn’t Emma with a colleague then, that’s fine, must keep a look out though. Jane/Amy arrived, ordered drinks, well at least Jane did, Costa don’t seem to do anything for a person with diabetes who doesn’t want to take any insulin at that moment. No-one else came in who looked like a rep, no-one else carrying anything. I thought about texting Emma but didn’t but looked over again at the ladies and noticed a tube on the table, scanning around I saw an Inset II infusion set. I went over and introduced myself. We’d been in the same place together for 20 minutes.

The other lady was from another part of Johnston and Johnston, who’s switching to the Animas side soon.

How to start a demo properly

I’d already prepared Emma by telling her not to talk about or demo filling the cartridge; to make sure needle sighting was kept to bare minimum; to make sure she brought pink infusion sets; to make sure she brought a pink Animas Vibe pump.

Emma looked Amy straight in the eye and said (something like) “Amy, how are you and what are you feeling about pumps at the moment?”, followed by “What are you looking forward to about getting a pump?” followed by “What are you even slightly worried about with the pump?”

For probably ten, fifteen or maybe twenty minutes Jane and I took a back seat and listened to their conversation. This was brilliant; exactly what we wanted; exactly what Amy needed; exactly what should have been done, well done Emma.

A pump of many colours

Emma got out five pumps, one brand new which she Amy to look at, hold and feel. The other four were the demo pumps and came in black, silver, blue and pink. Any guesses for which one Amy picked up immediately? It was pink. The only colour missing was green, but that didn’t matter as we’d seen Annie’s daughter’s green one a couple of weeks back. The green would be Amy’s second choice as it’s a nice looking colour.

On to the demo

Emma asked Amy what she does for a bolus at the moment and Amy spoke about her routine. We then ran through how that would be done on the pump. For once I was quicker on the buttons and menus than Amy, but that won’t last, she’ll soon be operating it and blurred-lightning-warp speed, so fast I won’t be able to keep up, so I’m chalking this up as a win for me 🙂

First bolus done, then another, then another.

Combo-bolusing

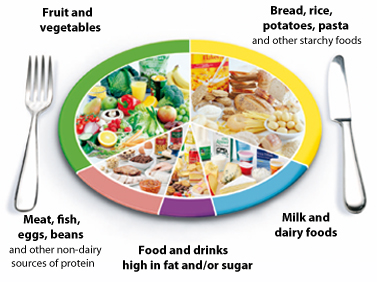

Emma demoed the different bolus types and spoke for a while about combo (or ‘split’) bolusing. The idea is that some foods take longer for the ‘sugar’ spike to happen, pizza for example and pasta meals, whereas others spike and drop very quickly, such as things high in sugar and low in fat.

This is not something you can easily do when on multiple daily injections (MDI), you literally give the insulin and it does it job in whatever time frame it works in. You give all the insulin in one go, normally before the meal or after, and the only way you can split bolus is to take two different injections. Name me a 12 year old who will be happy to do that!

It’s so easy to split bolus on a pump and makes so much sense, although I can’t make up my mind whether I’m just sold on this idea and it’s useless or whether it’s a damn handy feature. It seems to make so much sense.

I’m sure all pumps are similar but on the Vibe split-bolusing – or combo bolusing as they call it – is so easy: select the option; say how much (e.g 30%) you want now and how much (e.g. 70%) you want later; set the duration for the bolus (e.g. 4 hours); it’s done. The 30% (or whatever) will be delivered now, the 70% (etc.) will be delivered over the next 4 (etc.) hours.

So presumably the next ‘Carbs & Cals’ book will by ‘Carbs & Cals & Protein & Fat & SplitBolus’?

Basals and Temporary Basals

On MDI Amy gives herself about 13 units of Levemir at a set time each day and this lasts around 20-24 hours. Many people say less, others don’t, it’s a debatable area. One thing’s for sure though and that this Levemir is known as ‘basal’ insulin and has a long acting time, designed to get her through the day and mimic what a healthy pancreas does.

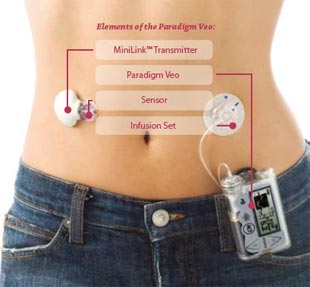

On a pump the big advantage is that no longer is a basal injection required as the pump dispenses a very small amount of fast-acting insulin (Novarapid, Apidra) every 2 or 3 minutes.

This advantage becomes even bigger when Amy is doing some sport as exercise will more than likely drop her blood glucose levels. With the pump you can set a Temporary Basal Rate (TBR) to overcome this, reducing the default basal rate by any percentage (in increments of 10). Setting a 30% TBR means she’ll only be getting 70%(ish) of her normal basal insulin for whatever period she chooses. When setting the TBR you not only decide the amount but also the length of time it’s active for, after which it reverts to normal.

Infusion set change

Jane and I had already done a set change with Annie a couple of weeks back, with Annie placing it on her arm for the first time. I didn’t step forward to be the subject last time but this time I’d decided I’d step up and be the test dummy. Amy didn’t want to do it on herself or on me, so Emma got out a couple of sponge-like pads.

Emma gave Amy an Inset II infusion set and took one for herself. Slowly she talked Amy through the process and explained some of the design benefits of the set. Amy was cautious but managed the change very quickly, although didn’t do one part correctly and the set didn’t stick the the pad. I could tell Amy was concerned this would happy all the time in real life but was assured it is normally ok. She did it again and it worked fine.

End of a great demo

A lot of questions from us and Amy later and the demo ended.

Emma had demonstrated the products very well, she’d answered every question we had, she’d reassured Amy of any worries, she’d confirmed all the good things Amy already knew. Thanks Emma.

Amy left there with a smile.

Animas Vibe pumps

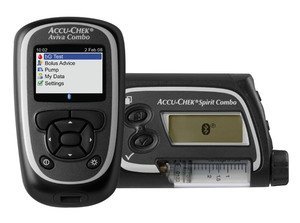

Animas Vibe pumps Roche Accu-chek Combo pump and meter

Roche Accu-chek Combo pump and meter Accu-chek Aviva Combo meter, almost identical to the Aviva Expert

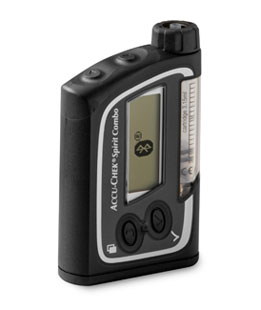

Accu-chek Aviva Combo meter, almost identical to the Aviva Expert The Accu-chek Spirit Combo pump

The Accu-chek Spirit Combo pump Rapid-d

Rapid-d Flexlink

Flexlink Tenderlink

Tenderlink The NHS Eatwell plate.

The NHS Eatwell plate.  There’s many rungs on the ladder towards the pump

There’s many rungs on the ladder towards the pump